Malik Ben Nabi

21:57

Introduction

Life of Bennabi

Bennabi’s Thought on Civilization

The Rational Stage |

Time of Ibn Khaldun |

Year 38 H. (Siffin) |

Bennabi’s Cycle of Islamic Civilization |

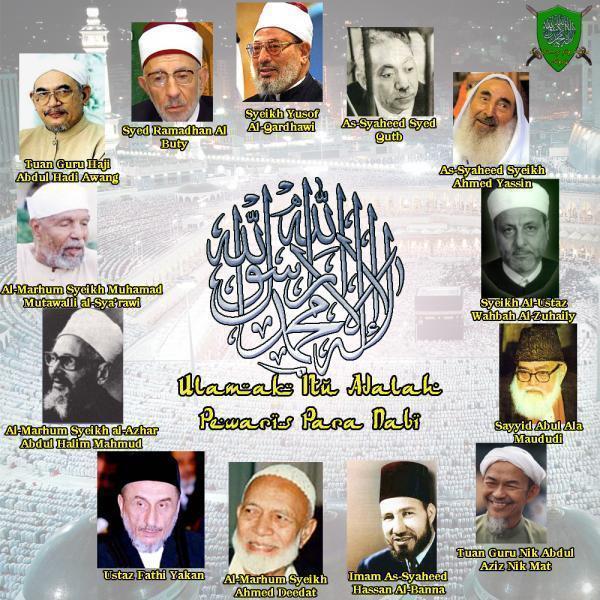

Ulama Pewaris Nabi

Rasulullah صلى ا لله عليه وسلم bersabda

إن الْعُلُمَاءُ وَرَثَةُ اْلأَنْبِيَاءِ، إِنَّ اْلأَنْبِياَءَ لَمْ يُوَرِّثُوْا دِيْناَرًا وَلاَ دِرْهَماً إِنَّمَا وَرَّثُوْا الْعِلْمَ فَمَنْ أَخَذَ بِهِ فَقَدْ أَخَذَ بِحَظٍّ وَافِرٍ

“Sesungguhnya ulama adalah pewaris para nabi. Sungguh para nabi tidak mewariskan dinar dan dirham. Sungguh mereka hanya mewariskan ilmu maka barangsiapa mengambil warisan tersebut ia telah mengambil bagian yang banyak.” (Tirmidzi, Ahmad, Ad-Darimi, Abu Dawud. Dishahihkan oleh Al-Albani)

Rasulullah صلى ا لله عليه وسلم bersabda

إِنَّ اللهَ لاَ يَقْبِضُ الْعِلْمَ انْتِزَاعاً يَنْتَزِعُهُ مِنَ الْعِباَدِ، وَلَكِنْ بِقَبْضِ الْعُلَماَءِ. حَتَّى إِذَا لَمْ يُبْقِ عاَلِماً اتَّخَذَ النَّاسُ رُؤُوْساً جُهَّالاً فَسُأِلُوا فَأَفْتَوْا بِغَيْرِ عِلْمٍ فَضَلُّوا وَأَضَلُّوا

“Sesungguhnya Allah tidak mencabut ilmu dengan mencabutnya dari hamba-hamba. Akan tetapi Dia mencabutnya dengan diwafatkannya para ulama sehingga jika Allah tidak menyisakan seorang alim pun, maka orang-orang mengangkat pemimpin dari kalangan orang-orang bodoh. Kemudian mereka ditanya, mereka pun berfatwa tanpa dasar ilmu. Mereka sesat dan menyesatkan.” (HR. Al-Bukhari no. 100 dan Muslim no. 2673)

"Jika engkau bisa, jadilah seorang ulama. Jika engkau tidak mampu, maka jadilah penuntut ilmu. Bila engkau tidak bisa menjadi seorang penuntut ilmu, maka cintailah mereka. Dan jika kau tidak mencintai mereka, janganlah engkau benci mereka." (Umar bin Abdul Aziz)

The Rational Stage |

Time of Ibn Khaldun |

Year 38 H. (Siffin) |

Bennabi’s Cycle of Islamic Civilization |

Kepada semua penulis asal, blogger atau sesiapa saja yang artikelnya saya petik dan masukkan di sini, saya memohon kebenaran dan diharap tidak dituntut di akhirat nanti. Seboleh-bolehnya saya akan "quote" artikel asal dan sumbernya sekali, supaya apa yang dimaksudkan oleh penulis asal tidak lari atau menyeleweng. Saya ambil artikel-artikel penulisan untuk rujukan saya dan sahabat-sahabat pelawat. Saya masih cetek ilmu tidak sehebat sahabat-sahabat yang menulis artikel-artikel di blog ini. Jazakumullah khairan kathira kerana sudi menghalalkan ilmu untuk perkongsian seluruh masyarakat Islam

0 comments